Chapter Five:  (Volume I)

(Volume I)

ORIGIN AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF SOVEREIGNTY

Chapter Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

Traditional international law accords a very strong and fundamental position to governments deposed by a usurper. The essence of the natural law, upon which international law is based, is twofold: might does not make right and it is ultra vires to overthrow what God in his providence acting through the course of history has revealed to be the natural constitution of a particular nation.

The international law concerning de jure sovereignty arose from the historical situations in which monarchs were unjustly dethroned by a usurper. In order to appreciate the very strong positions that de jure legitimate governments have under international law vis-à-vis usurping de facto administrations, it is necessary to have an understanding of the moral right to authority possessed by sovereign royal houses under the natural law. Needless to say, a traditional republic legitimately established under the natural law has the same moral and legal right to de jure sovereignty as that possessed by a sovereign royal house, but its moral right to authority is more directly demonstrated organically by the governments from the position of sovereign royal houses.

Sovereign Royal Houses

Sovereign Royal Houses

The moral position of royal houses to de jure sovereignty is derived from the origin of the nation out of the family as the most basic unit of society. Fatherhood was naturally important in the development of kingdoms. The patriarchal nature of kingship is obvious and is scripturally supported as a natural, even divine, development in the history of mankind:

Even the Power which God himself exerciseth over Mankind is by Right of Fatherhood, he is both the King and Father of us all; as God hath exalted the Dignity of Earthly Kings, by communicating to them his own Title, by saying they are gods [Psalms 82] – so on the other side, he hath been pleased as it were to humble himself, by assuming the Title of a King to express his Power, and not the Title [like President or Prime Minister] of any popular Government; we find it is a punishment to have no King, Hosea 3:4 and promised, as a Blessing to Abraham, Gen. 17:6. that Kings shall come out of Thee.[1] (emphasis added)

“All Power on Earth is either derived or usurped from the Fatherly Power, there being no other Original to be found of any Power whatsoever. . . .”[2] “The Right of Fatherly Government was ordained by God for the preservation of mankind. . . .”[3] This is the natural beginning.

Origin of the Nation Arising Out of the Family

Origin of the Nation Arising Out of the Family

Historically, anthropologically, and socially the nation originated out of the family, which is the basic and most fundamental unit of society. The family is, by far, the most important organization in all ages. It is no less than the brick and mortar of civilization. Strong families equal a strong nation. A state or kingdom can only be as strong as its essential component parts. Hence, the family has been called the matrix, even the headwaters or fountainhead of all humanity. The highest, most elementary form of human society known to nature is the family, which includes the extended family consisting of parents, children, grandchildren, and other immediate blood relations. This organization constitutes one definite, well-defined unit.[4] “The family is frequently referred to as the social cell out of which the community develops. The metaphor accurately describes the relation of the family to the body politic.”[5] The term family also includes supporters, retainers, and followers as well as blood relations:

Aristotle wrote that the first human association is between male and female, the second between master and servant and that both of these arise from the natural wants of man, and the two together form the family. The term family has a wide scope of meanings and does not always refer to a little group of parents and children. Consanguinity is usually the identifying and unifying element in the family, but in ancient times other persons than those united by blood – ties were considered members, and as such, had definite rights and obligations. The old Roman type of family, for example, included not only the blood relatives, but also slaves and servants, comprising in all, a large social group. In primitive times the family was usually a large group.[6]

Nature itself demonstrates that the family is the basic or organic unit of society. This is true of the natural family as well as of the supra natural family formed by those who enter religious communities. We find the familial organization of society implicit in the social nature of man:

He is a social being in a twofold sense. He is a sexual being, that is, male and female. Men and women are coordinated for the sake of propagation and preservation of their kind as well as for mutual help and completion. For a better and higher life they do and must form the community of marriage and family, consisting of man and wife, parents and children. Each human being is man or wife, father or mother, son or daughter, each is in some way the member of a family. And even where we “leave father and mother, brother and sister, for the kingdom of heaven,” we enter a spiritual community that speaks of itself as a family, where we are brothers and sisters. Thus even where the natural form of the family is sacrificed, the spirit of the family, the moral order and the affectionate bonds of the family, are still a kind of prototype. The plurality of the families and their mutual coexistence now lead to a second and higher form of social life, to the political community. Its end is to produce a sovereign order of peace and justice under the protection and furtherance of which the preceding and pre-existing forms, the family and the person, can live and function according to their own essence.[7]

Indeed, the natural purpose of human existence is exclusively found and circumscribed in, by, and through the family:

The Schoolmen called it vita economica: life around the house, the homestead of the family. Its end is the preservation of kind in the procreation of children and in their care and education by the parents. Apart from the care for material economic goods, that embraces the care for spiritual goods, the education of the mind and of the will to the virtues, individual and domestic, to charity and to obedience, to piety and to sacrifice, to justice and to love. There exist, therefore, original rights for the parents in order that they may fulfill their duties: the right of the parents to define the education of their children; the right of the sacredness of the family’s home; the rights of paternal authority.[8]

Nature of the Family

Nature of the Family

Among the most interesting and informative studies of the family made in modern times are the various social and anthropological analyses undertaken by Sir Thomas Innes of Learney (1893-1971), the Lord Lyon King of Arms, who was the chief judicial officer of Scotland responsible for maintaining the scientific study of the recognized families comprising the Scottish Nation and the organization of such families through anthropological family totems, which are objects or living things that a group regard with special awe and reverence.[9] Sir Thomas has eminent practical experience and anthropological knowledge concerning the family systems, which are known in the Highlands of Scotland as “Clans.” (The term is interchangeable with that of “Families.”) He speaks of the family or clan as being a social group consisting of an aggregate of distinct families actually descended or accepting themselves as descendants from a common ancestor:

The word “clan” or clanna simply means children, i.e. the descendants of the actual or mythical ancestor from whom the community claims descent, in so far as these remain within a tribal group which, as a social, legal, and economic entity, is treated as a unit. In the Middle Ages, law and custom did not treat of individuals, but of groups. The earliest groups were personal and pastoral, but as soon as a group settled, the territorial influence of the land which it had occupied affected its structure. Both the group and the land were called after the chief, who in theory was actually owner of the whole group and of the land of the group, with absolute power over every member, though in practice along with a “family council,” for hereditary and familial rule (i.e. monarchial and clan systems) are always more “constitutional” and free than the sway of republican electees of any description.[10]

Membership in such a family was symbolized in the possession of certain family totems or symbols that represented both the whole family and the individual’s place within the family through slight variations of the basic family totem, known as marks of cadentry. Possession of such totems seemed to be universal to family groups in all times and places.[11]

Possession of a totem undifferentiated by such marks of cadency indicated the founder or eponymous of the family, that is, the one who gives his name to a family and/or place.[12] Adoption into the family was accomplished through “bonds of manrent” (a covenant of vassalage, loyalty, and full acceptance) and was a recognized feature of family law.[13] This was responsible for the rapid multiplication and expansion of certain ancient families.[14] In Europe, the science of families, their organization, their position within the whole community, and the study of their totems or symbol is known as heraldry.[15] In Japan, such totems are known as “mons.” The use of such hereditary totems or arms is very important for the identification of the family and indicates their origin from a common parent.[16] In Europe, such heraldic totems are a symbol of both the recognized family itself and of the individual within the family. Heraldry is, thus, the anthropological science of the family and its organization.[17]

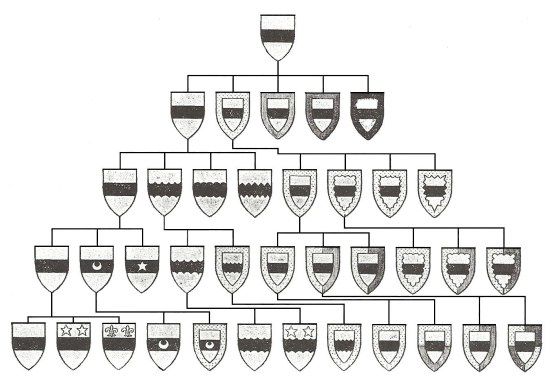

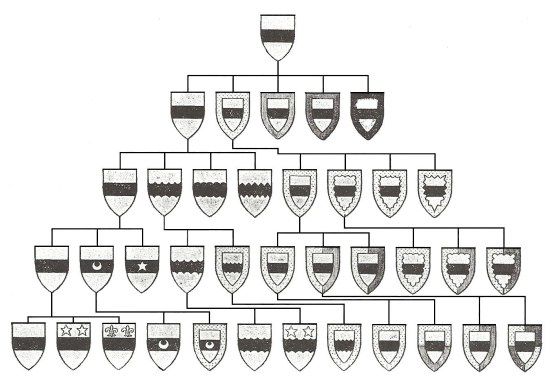

These totems were a very useful device for illustrating the family itself as a distinct group as well as the organic or natural (as opposed to artificially created) organization or conduct of a business within itself. A schematic diagram of such totems by Sir Thomas very clearly illustrates how the family is organized. The plain or undifferentiated totem indicates the founder or eponymous of the family, while the totems differentiated by various marks of cadentry illustrate the various descended branches of the family and the sub-branches within each of these. Thus, each member of the family has his or her own distinct variation of the basic family totem. As new members are added to the family through birth (or adoption), a differentiated version of the basic totem is assigned to each individual and represents his/her exact place within the family and the relationship that exists with other members. A person familiar with the family totem system of heraldry can actually “read” an individual’s totem and ascertain what family he/she belongs to and the position held within it. It would not be out of place to say that the individual differentiated totem represents the person himself, while the basic design of the totem represents the entire family. (See Chart below).[18]

A careful examination of this schematic totem diagram shows that the family was organized on the basis of a pyramid.[19] It will be noted that the individual totem descends from father to son. So it can be said that the son “represents” the father. The basic or undifferentiated totem attributed to the founder or eponymous of the family descends (in normal circumstances) to his eldest son as his representor. The whole idea of a family necessarily connotes a biological and hereditary group clustered around a hereditary stem of the founder or eponymous.

The family grows in expanding branches from the founder downwards. Each branch group forms its own community within the family and the individuality of each group is indicated by marks of cadentry or differences on the basic family totem. Nevertheless, the blood of all flowed in each member and was often renewed by marriages between members of different branches within the family, giving the family (and later the nation) its own distinct features.

The authority of the father or eponymous over his children was not conferred upon him by some other human person or persons or by an election. It did not exist in another before he received it in the first instance. The father’s authority can only exist in himself. It springs not from some external source but from his position as father, of which it is a natural and inseparable attribute. As this authority is the natural attribute of the position of the father, it must be regarded as residing ultimately in God, the Author of Nature, and conferred by Him on the father who has the legitimate natural right to its possession and exercise.[20]

As this authority springs naturally from the father’s position in the family – just as the attributes of a body spring from the inner nature of the body – and is not conferred on him by anything external to himself, we may declare that the father’s authority is conferred directly on him by God under the natural law, which is discoverable by all men in all times through the use of self-evident rightful reasoning. In essence, then, the father’s authority over the family arises from his designation by God’s revelation of Himself through His providential direction of human affairs: The father receives his paternal authority over the child from God under the natural law by the fact that a child is born to him. In this case, the designation of paternal authority came naturally from God, who normally chooses to reveal His will to man by directing natural and historical circumstances. There is no supranatural designation of the father through a vision or miraculous intervention. God acts just as directly and obviously when He acts through the natural law as He does when He reveals His divine will through Revelation.

In this case, the father’s authority over the family comes immediately and directly from God under the natural law. Thus, the father’s authority over the family under the natural law (the natural order or being of things in the universe) is “by the grace of God.” This natural order of things is specifically supernaturally confirmed by God in the Fourth Commandment (Fifth Commandment in the original Bible) on honoring thy father and mother, but it would nevertheless be just as binding on all men in all times under the natural law, even if it had not been divinely revealed.

A fatherless or orphaned family is an imperfect group. Without unity at its center or core, it would have soon dissolved, having no one in authority over it, and would have not been able to resist disintegrating pressures from without. The father is indeed the link connecting all members of the family and their branches to each other. In his person, therefore, the father represents the integrity or unity of the family, as a distinct social group. As Sir Thomas anthropologically explains this situation, “continuity under the bond of kin embodied in the preservation of the parental tie is the whole basis of the clan concept.” Thus, a fatherless family is a sorry organization, alien to the whole idea of civilization, wherein the father is the sacred embodiment and personification of the family as its founder and leader. Hence, the question of succession to the father is necessarily of the utmost importance and widest interest to all members of the family.[21] The importance of the father to the continuance of the family as a viable organization can clearly be seen from the anthropological and sociological analysis of his position within the family:

All tribal groups and all subdivisions of these are conceived, by the men who compose them, as descended from a single male ancestor, or sometimes a matriarch. Not only was the tribe or sept named after this eponymous, but the territory it occupied derived from him the name by which it was most commonly known. Upon the death of the eponymous, one of his descendants became the “Representor” of him and of the group which was “his,” i.e. within his patriarchal potestas. The successive chiefs were the judges, public officers, and representors of the group, and the very name king or king means the head of the kindred. This chief or primitive “King” formed the centre and sacred embodiment of the race, i.e. the supreme individual of the race giving to its race – ideal the coherence and endurance of personality. Whilst the chief’s influence was personal and tribal, he owned an official estate or earbsa which descended only along with the chiefly office, and for these territorial chiefs and chieftains to achieve the rank of aire deisa it was necessary to be “the son of an Aire and the grandson of an Aire,” and to hold “the property of his house,” or at all events the principal dwelling-place. Sir George Mackenzie explains (expressly in relation to undifferenced arms) that:

“By the term ‘chief,’ we call the representative of the family, from the French word chef or head, and in the Irish (Gaelic), with us the Chief of the Family is called the Head of the Clan.”

The ceann cinnidh or clan chief – or more properly the “Head of the Clan” . . . is thus in nature precisely the same as the chief of the family. Both are the living individual who represents the founder of the tribe, and who is the sacred embodiment of the tribe itself.[22] (emphasis added)

The father or patriarch is, therefore, the parental representative of the founder and the sacred embodiment of the family group. The successor of the founder or eponymous thereby acquires authority over the entire family in loco parentis. The maintenance of the family as a working institution depends on this. The family is community-based on the assumption of heredity and a “parent and child” nexus. As Sir Thomas states, the constitutional authority of the successor of the founder or eponymous of the family was derived from his “representing” the eponymous. The patria potestas was not derived from the “children” any more than the chief’s derived from his clanna.[23] Thus, it appeared that the patriarch or chief of the family took the place of the original father:

Whilst the chief, or chieftain, “was the law,” as Lord Aitchison has expressed it, he derived his patriarchal authority not from his children but from the parental relation to the community, as Sir George Mackenzie so emphatically illustrated in his treatise on the Scottish monarchy.[24]

The nature of this parental succession is that what passed from patriarch to patriarch was the “family community” as a “going concern.” That is, “the public responsibility comprehended in the term family.” In many tribal communities it lay with the patriarch to determine which member of the family, natural or adopted, should succeed to the public office of the patriarchate.[25] “It was nevertheless strictly hereditary and by whatever means ascertained . . . the ‘head of the central or stem family was the chief’ of the clan.”[26]

This family principle emphasized the patriarchal chiefly element in which the chief was the parent, ruler, landowner, and proprietor on behalf of his clanna or children. This parental aspect is implicit in the very term clanna, which negates at the idea of “elected chiefs.”[27]

Since the clan chief represented the founder of the family, he succeeded, upon his predecessor’s death, to the insignia of the eponymous that represents the original, self-derived, parental authority of the founder. The succeeding patriarch or “representor,” and he alone, was entitled to bear the plain or undifferentiated totem of the family. Any other course would have wrecked the whole value of totem symbolism (heraldry) and in warfare (where members of the family bore their particular totem on a shield) would have rendered it a danger to the entire family survival.[28] In the course of time, possession of the plain or undifferentiated family totem represented parental succession to the original founder as the family patriarch, who, as Sir Thomas stated, was the “representor” or sacred embodiment of the family itself. The patriarch or chief was looked on by members of the family exactly as a father, corresponding, thus, to his actual constitutional position as “representor” of the founding father:

In every respect the chief was regarded by the members of his clan not as a master or landlord, but as a friend and the father of his people. To quote the description of the similar organization in olden France:

He commanded the group surrounding him, and, in the words of ancient documents, “he reigned.” The family became a fatherland designed in ancient documents by the word patria, and was loved with the more affection because it was a living fact under the eyes of everyone.[29]

Thus, anthropologically, the patriarch or chief “reigned” over the family, and Sir Thomas describes how family chief succeeded family chief in the same manner as in a royal house. He strongly supports the historical analysis comparing a chief to a sovereign prince and the description of family chiefships as “little sovereignties”.[30]

The mode of succession to the office of patriarch or chief as the “representor” of the eponymous or founder of the family was hereditary, being derived in Scotland from “a combination of the pictish order of succession, the Hebraic Code (Numbers 27: 4 and 8; 36: 3), and the Roman gens” as follows: “by which ever was at the time being the next descendent, that is, a son or a daughter, a nephew or a niece, the nearest then living. Failing there, however, the next heir begotten of . . . a collateral stock [would be chosen to succeed].”[31]

This mode of succession seems generally to be written into the hearts of men in all times and places. It is the embodiment of the organic idea that the first-born son or daughter is naturally ordained to represent the father after he is called from this world to the next. This arises from the idea that since the first-born is the first child to be given to the father and thereby the closest to him in generation, he or she is naturally intended to succeed the father. This is true even in egalitarian America, which unlike Europe has no laws on this subject. Witness, for example, the very common occurrence although more common in the past of the first-born working to support the mother and younger children in the event of the premature death of the father. There are no civil laws compelling him to do so, and he is legally free to abandon the mother and younger children to go off on his own. Yet he does not do so out of the moral conviction that it is his obligation as successor of the father as the head of the family due to his position as the first-born to so provide for them. Moreover, the mother and younger children look to the first-born in these circumstances in expectancy of support. This moral conviction, written so strongly on the heart that it defies even the written positive law derogating from it, is what we call natural law, which is riveted in the heart of all good men, unless that person was unworthy.

Hereditary succession seems to be the mode of succession designated for the family by the natural law. However, it was not immutable primogeniture, and in the case of an unsuitable son, the succession could be designated by the incumbent patriarch to a more suitable son. This is “a useful and age-old patriarchal principle.”[32] In Scotland, this practice of designating the successor is known as Tanistry, and it was a form of testamentary succession[33] as opposed to intestate primogeniture succession. Moreover, if the heir proved to be a very unsuitable or incapable person, the family would use its influence to get him to resign in favor of a more suitable nominee, which was usually the next heir of the line.[34]

This Scottish mode of succession came to be known as the Law of Arms since the family totem was incorporated on the war shields of family members, and it later evolved into our present coat of arms. The Law of Arms applied to all recognized families other than outlaw bands living on the extremities of recognized family groups.[35] It appears that hereditary succession under the Law of Arms, including intestate primogeniture succession and testate designation of the heir from the central or stem family group, was the normal mode of succession, and it completely precluded succession by election. The only time when election was admitted was in the rare instance when the central or stem family became extinct. At this point, the chiefs of the various branches of the family gathered and selected one of their number as patriarch. This renewed the hereditary nature of the “representor” in his branch. To elect the chief or patriarch in the normal course of events would be completely contrary to the essential nature of the family and its natural dignity.[36]

Both the succession and the government of the family were indicated by its essential nature. Each branch of the family was founded by the younger sons as they came off the main line. At the head of these branches would be a sub-chief or chieftain whose relation to the members of that branch is the same as that of the patriarch to the whole family. “The chieftain is simply ‘representor’ of the ‘first raiser’ of the branch.”[37]

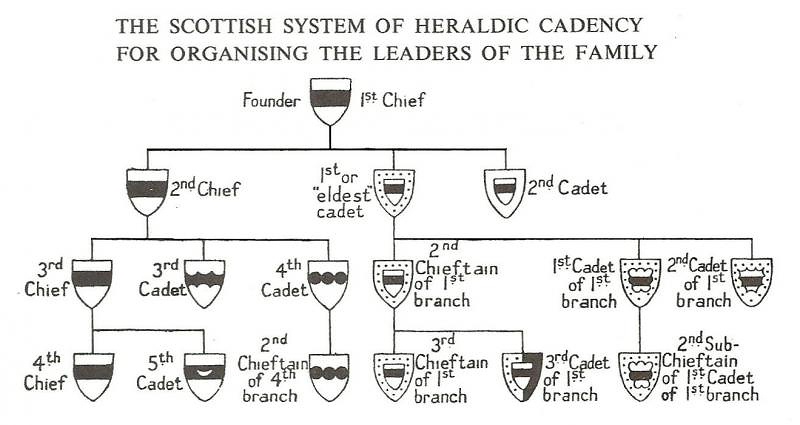

The chieftain or sub-chiefs would receive a variation of the basic family totem that would represent his branch, and all members of his branch would bear a variation of its version of the family totem. The chieftain sub-chief representor of each branch of the family formed a branch government of the respective family and served as a councilor or advisor of the family patriarch over all the branches. The following illustration explains how the family is organized and governed along natural or organic lines:[38] (See Chart below).

Patriarchal government was always what would be today termed “constitutional” in practice and did not involve the absolutist arbitrary irresponsibility so popularly supposed by revolutionary propagandists against monarchy and/or a patriarchal government:

Whilst the supreme, and parental, power lay in the chief, as hereditary and reigning ceann-cinnidh (subject, of course, to superior chief or king, in matters “wherein these stood patriarchally” in relation to him), he was entitled to, and fortified by, the advice of his council. A chief was no tyrant for an hereditary monarchy always tends to be in practice “constitutiona1,” however absolute it may seem in theory. As Mrs. Grant of Laggan says:

Nothing can be more erroneous than the prevalent idea that a patriarchal chief was an ignorant and unprincipled tyrant. . . . If ferocious in disposition, or weak in understanding, he was curbed and directed by the elders of his tribe who by inviolable custom were his standing council without whose advice no measure of any kind was decided.[39] (emphasis added)

Indeed, as Sir Thomas points out, one of the principal duties of the family council was to see that the patriarch “never forgot” his duties “to look after the preservation of the family and family property of which he is the representative” and to maintain the patrimony of the family “to be handed on in its integrity to the next heir.” The family council, organically composed of the branch chieftains, functioned to ensure that the patriarch or chief of the family, possessing supreme parenta1 authority over the family, “was permeated with the feeling that he was directly responsible not only for his own destiny, but also for that of his kinsfolk.”[40]

The family council was an organic “aristocracy” of the family due to its derivation from the “representors” of the natural biological branches of the family, and it served not in derogation of the authority that the patriarch or “representor” of the whole family held, but the council naturally served as advisors and counselors. The family council was a recognized feature of family organization throughout Europe:

In the greater continental houses, such as those of the princely and countly families of Poland, etc., these “councils” not long ago were formal and stately gatherings – in the full panoply of a “family parliament” which deals with the administration of the family estates, trust funds, investments, and so forth, including arranging matrimonial and testamentary affairs, and occupations of members of the family. Indeed, in Scotland, such family councils operated in many such matters at any rate well into the nineteenth century; and in the annals of county families transactions are recorded as decided on, and careers of children settled by deliberation of, and decision in, such family councils well into the middle of the century. Whilst the ultimate “family laws” were made by the chieftain, be it observed that if he were “prodigious and misguided” it was competent for the family councillors to resort to the next higher chief, or to the king, to have the incompetent chef de famille put under “interdiction,” or, if necessary, in ward.[41]

The above illustrates the complete constitutional organization of the family as an on-going natural community of people going back “from time whereof the memory of man was not.”

Derivation of the Nation from the Family

Derivation of the Nation from the Family

The family does not remain static. The children of the eponymous marry and add new branches to the family. This, in turn, begets an environment in which the division of labor and exchange become possible. Out of this grows a higher or more developed life and culture. A military organization is created for providing protection from enemies without. Likewise, an economic organization is created to barter for supplies from without. Above all, a juridical organization arises in the form of the patriarch and his family council. This provides a body of common law for organizing and directing the resources of the family community. Aristotle refers to this expanded family as the “village community.” It represents a distinct advance on the simple family out of which it sprang, and it represents also the first distinctive shape in the development of the State out of the family.[42] A natural law analysis indicates that the simple family thus widens into an expanded family of the village community, which in turn acquires the self-sufficiency necessary to evolve into the State:

The family was not the only possible origin of the State, but it was the most natural origin. “The most natural form of the village,” writes Aristotle (and, we may add, since the most natural so also the commonest form), “appears to be that of a colony from the family, composed of children and grandchildren.” It is, therefore, right to speak of the State as normally originating in the family through the medium of the village-community.[43]

The nuclear family thus grew into something more than a mere family. It grew into a tribal group or clan of persons related to each other by blood. “The whole group would be characterized by a community of blood, and as a rule by a common name.”[44] As pointed out earlier, there would be a common totem as the symbol of the unity and integrity of the tribe and its descent from a common founder.

Intermarriage would solidify different allied tribal units into a single homogeneous group. Certain marked physiological and psychological characteristics would appear, such as (1) a common speech; (2) a common religion; and (3) an identity of economic needs. All of this would produce a common life and spirit with identity of hopes, of interests, of professions, and of dislikes. The common history of the group would produce a common tradition and common sympathies arising out of the same triumphs and sufferings in the past.[45] When the degree of cohesiveness was so great as to create a permanent tendency to complete self-dependency from other communities, the expanded family-tribe was then a nationality:

Nationality in its fullest sense may therefore be defined as any large community descended from a common stock and possessing such a large number of common characteristics and interests as makes it racially one and distinct and sets up in it, or at least in such portions of it as occupy a distinct territory, a permanent tendency to political unification under a distinct ruler.[46]

Nevertheless, in the political understandings of peoples, generally “the most potent element going to constitute a nationality is accepted to be identity of blood and the recognition of a common descent.”[47] As the extended family evolved into a nationality, so, too, the original organizational structure of the family evolved to meet the needs of the growing community:

When the family group, therefore, has grown and developed into a tribal society, we have the beginning of “political” organization. Size itself is of some importance and the multiplication of persons within a group would give rise to the necessity of some form of quasi – government. Customs and traditions, developed through centuries, become part of the daily life of the people, the warp and woof of their mode of existence. Authority is necessary for the observance and maintenance of customs. The line of demarcation, however, between the parental authority of the family and the political authority of the State, is not easily discernible.[48] (emphasis added)

However, like all things in nature, the origin of the State out of the extended family was not a sudden occurrence. Its evolution was one of gradual growth and the result of a very long process of development. Each stage of its growth was the result of the conscious effort on the part of the family to meet the growing needs of the community. The state was therefore a natural or organic growth, growing to some extent as plants grow, spontaneously and independently of the contrivance of reason or human plan.[49] It nevertheless grew in response to a divinely implanted purpose within itself in the same way that an acorn grows into an oak tree. Thus, from a single family it extended itself into a larger body of kindred into a nationality that became the state or nation, accompanied all the while by recognition of superiority in an individual or in some part of the greater family as specifically representing the original parent. The State retained the constitutional form of the family out of which it evolved:

Having developed out of the family, the State would, in the beginning, and for a long time afterwards, retain the outward forms of the family organization, for instance, the monarch might be the patriarch of the community, and it would retain these forms for one particular reason, viz. on account of the strength and the rigidity which the family organization imparted to society.[50]

In this connection, it can be observed that:

. . . in those cases where we are able to trace the history of states further back, the starting point seems not to be a condition of universal confusion but a powerful and rigid family organization. The weak were not at the mercy of the strong, because each weak man was a member of the family, and the family protected him with an energy of which modern society can form no conception. . . .[51] (emphasis added)

The origin of the state must be traced back to the family as the original social group from which, in turn, tribal and village life developed through kinship and land ownership, and it resulted gradually in the formation of political society.[52] The state, therefore, developed out of the family to achieve the practical ends of mankind:

From all this it is clear that the State is a natural institution, an integral portion of the design of nature, and not a product of chance or convention of any kind. It is natural, first, because it is founded on the most natural of all social institutions, the family. Secondly, it is natural because it grew out of the family naturally, the State being nothing more than the natural expansion of the family. As the family developed, without formally aiming at the State, it approached nearer and nearer to the condition of a State. The State was only the flower that marked the coming to maturity of the expanding family.[53]

More complete historical, sociological and anthropological proofs for the natural law origin of the State in the family are to be found in Fr. Cronin’s text, The Science of Ethics, vol.2, footnotes covering pages 478-479.

When the extended family evolved into the nation and developed its forms, it divided up the territory of the nation on a military basis, usually among the chieftains and sub-chieftains of the extended family. These territorial divisions were known as “marches” and “counties,” from which were derived the titles of marquise/marquess and count for their chiefs. The really great chieftains were called leaders or “dux,” from which come dukes, while the smaller units were known as baronies. In time, these leaders came to adopt or were granted their own totem to distinguish their branch of the nation and their territories. The national totem remained the symbol of the nation and continued to be used by the central or stem part of the greater family of the nation whose chief, the patriarch, was known as the king. The national totem or symbol continued to be used as the insignia of the national army and for other national purposes; the leaders of the nation would incorporate it into their military pennons or banners to identify their nationality. This complete historical development gives us the institutions of the modern European nations and other nations as well.

It can be seen from this exhibition that the nation extended into being naturally from the eponymous family through the providential direction of the natural historical circumstances that gave rise to the nation and designated its institutions. In this natural organic development of the nation, we can see the omnipotence of God revealing Himself in history through secondary course. This is not to say that God founded the nation by a direct divine intervention. In our Judeo-Christian tradition, this occurred only twice in the instance of King Saul and King David. However, even here, God chose for the most part to work through natural historical circumstances to reveal His will – intervening miraculously only in very extreme circumstances. Theologically, God normally works not through direct intervention but in secondary causes through the direction or providential guidance of human circumstances to accomplish His will. His providential direction of revealing Himself in secondary causes through historical circumstances acts as a divine demiurge to indicate His design for the natural order of things. The natural law is no less God’s will than Revelation and is discoverable by men through the use of right reason; in this case, His direction is seen in the historical development of the nation and organic or natural evolution of its institutions.

Invalidity of Other Theories of the Development of the Nation

Invalidity of Other Theories of the Development of the Nation

Alongside the natural law theory of the origin of the nation from the extended family is the theory that gave rise to the French Revolution of 1789, the Communist Russian Revolution of 1917, and is cited in the justification of proletarian revolution everywhere. This is the theory of the origin of the state promulgated by Thomas Hobbes, perfected by Jean Jacques Rousseau, and applied in practice by Robespierre, Lenin, and Chairman Mao: The social contract theory under which the authority of the state is exclusively derived from a social contract by the masses. Under this theory, the authority of the state is originally vested in the proletariat and could have only been conferred upon the rulers through a compact between members of the proletarian masses.

This is diametrically opposed to the natural law theory whereby the authority of the patriarch arises naturally through his position as the representor of the eponymous or founder of the family that later extended itself into the nation. His authority arises not from any external source (i.e., the consent of the proletarian masses) but from his position as the representor of the original or founding patriarch. As this authority is the natural and inseparable attribute of the position of the patriarch, it must be regarded as residing ultimately in the Author of nature and conferred by Him on the patriarch, who has the legitimate right from his patrimonial position to its possession and exercise. As this authority springs naturally from the patriarch’s position as representor of the founder of the extended family or the nation, we can say it is not conferred on him by anything socially external to himself. Birthright gave him his honor and privilege. Thus it can be said that the patriarch’s authority is conferred on him “by the grace of God” by birth.

Needless to say, the social contract theory of popular sovereignty rejects God, regards Him and religion as superstition or “the opiate of the people,” and bases governmental authority solely on the consent of the masses. But, as was shown:

Natural authority is never derived from the “consent of the governed.” The most basic natural authority in society is the authority of parents in the family. Parents are not elected by their children. Parents do not hold authority over their children because their children have voluntarily contracted, or otherwise consented, to being under their authority. Parental authority is natural, derived from the very nature of the institution of the family, and reinforced by millennia of prescription and precedent.[54]

According to Hobbes, man lived in a “state of nature” that could best be described as dog-eat-dog where every man was every other’s enemy, a condition directly contrary to the idea of brotherhood, even of blood, between men.[55] The “state of nature” theory more properly describes a condition of supreme chaos and anarchy rather than that of man (even primitive man) endowed with a divine spark called the conscience and the potential for right reason. The “state of nature” theory is one of extreme competition between men in which no conception of brotherhood or social responsibility could be possible; as such, it is appealing to liberal capitalists. In this condition, men kept “their weapons pointing, and their eyes fixed on one another.”[56]

In summary, man in the “state of nature” is not a rational being, but he is literally an animal devoid of all obligations towards himself or others and without rights or duties. He is in a state of continual warfare and uses whatever means he can to attain his immediate end. In short, he obeys the law of the jungle and is an enemy to God, right reasoning, and everyone else. No unethical action can be condemned for such, because man has no ethical ideal written on his heart, no notion of what is just or unjust, or innate conception of right or wrong.[57] This atomistic individualism is the Liberte (license to do anything) of the 1789 French Revolution. It is in direct contradiction to the natural law theory of man’s existence under which man, by virtue of his creation by God has both natural divine rights and obligations.[58] Under the “social contract” theory as promulgated by Hobbes and approved by Rousseau, man moves from this state of supreme chaos to form a society by giving up his atomistic individual rights to form the state.[59] (Note the difference in terminology: the organically evolved nation vs. the man-made state.)

The “social contract” theory of popular sovereignty was amplified by Rousseau. According to Rousseau, political power (sovereignty) is a mere human convenience existing by an agreement between men. It derives not ultimately from God but from the sum of individual sovereignties on the State. Therefore, everyone might regard himself as a founder of the State and interpret the terms of the contract as he chooses; for, according to Rousseau, “each one is united to all, but nevertheless obeys only himself and remains as free as before.”[60] This idea is criticized as being absurd in theory and politically dangerous, because if any individual refused to yield his share of sovereignty and independence, government would become entirely impossible.[61] Respecting the essential nature of the society created by the “social contract,” Rousseau declares, “The social order . . . does not come from nature, and must, therefore, be founded on convention; since no man has a natural authority over his fellow men and force creates no right, we must conclude that convention, forms the basis of all legitimate authority.”[62]

The chaotic “state of nature,” which supposedly existed before men founded the “social contract” erecting the State, is lacking in historical foundation and is purely imaginary in character. It does not consider the family, which is the root foundation of all society. In other words:

Both Hobbes and Locke were wrong . . . in believing individualism to be man’s natural state, and society to be the artificial creation of individuals contracting with one another. Society is man’s natural state because the family, which is the building block of society, society in miniature, is prior to the individual. It is the individual, isolated and alienated from society, who is unnatural.[63]

For those who accept the Judeo-Christian religious tradition, a complete refutation can be found in Scripture, which depicts man as a fully rational, family-oriented being. In the one instance when the individualistic freedoms of the “state of nature” were exercised, the incident of Cain and Abel, the former was driven into exile and branded with a special mark of iniquity on the ground that he was indeed “his brother’s keeper.” Anthropologically and historically, the alleged “state of nature” theory is untenable:

Now it will not be necessary here to attempt to criticize the theory of the state of nature regarded as a survey of the actual early history of man, since that theory is now disproved utterly by what is known of the origin of the State, and it is not now regarded as worthy of consideration by any school of writers. Before the State appeared, primitive men were organized (as primitive societies are organized even now) into societies held together by a force which was far stronger than that of the unifying forces present in any State, vile the force of the blood-tie and of the authority either of the pater-familias, or of the combined heads of the tribe. In many cases the whole community would consist of a single family composed of parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren, and the collateral relations – all governed by a patriarch; in another case three or four of these tribal units would combine under the joint rule of their numerous heads; but at no period was humanity made up of isolated individuals, living under no ruler, and aiming at no sort of common good. The tribes that constituted the earliest societies were organized under their respective heads not only as families but also as incipient States.[64] (emphasis added)

Likewise, regardless of the physical or bodily evolution or of social conditions, man has always known the natural law that gave him rights and imposed obligations.[65] Even in his primitive state, man has always had right reason written upon his heart, thereby enabling him to discern right and wrong. This faculty of reason is what distinguished man from the animals, who do indeed live in the “state of nature” so described. Moreover, if an individual was so lacking in conscience that he did not bother to reason, his family members would take measures to ensure that his reason was righted:

Now this theory of universal war and universal unmorality is wholly imaginary and wholly false. In the period that proceeded the appearance of the State, individual was not at war with individual, because, being members of one family, their interests were largely the same. Each community consisted, then, of one immense family. Wives or husbands were, of course, taken from outside. In some cases the wife came to live with the man’s family; in other cases the man went to live with the woman’s family. But in every case the community constituted a single family unit. Their interests, therefore, were common, their land was common in the sense that it was vested in the family or the head of the family, and, as one eminent modern sociologist tells us, they defended one another in case of aggression from without with a fierceness and determination that are unknown today. Within the family community, if disputes arose, they were decided by the head, i.e., the patriarch. The patriarchal theory of ancient society or something akin to it is now universally accepted. As Sidgwick explains, it “emerges spontaneously” from what we know of the family basis of society in the past. The theory of the war of all with all is, therefore, far less applicable to the early period here in question than to the condition of society today.

Again, it is absurd to say that before the State appeared there were neither rights, nor laws, nor “mine” and “thine.” In that period men were ruled by the natural law just as they are now. There are innumerable laws and rights that have no dependence on the State, e.g. the law of fidelity between husband and wife, the right of the parent to the respect of the child and of the child to the support of its parents. Before the State arose there was also a “meum ac tuum.” A man had a right, at least, to the things produced by his labour. In the primeval period, therefore, it is untrue to say that rights did not exist. Indeed, as Kant remarks, unless in that period there existed rights of justice the State would not have been deemed necessary for enforcing these rights, and it was the enforcing of these already existent rights that, according to many defenders of the social-contract theory, was the primary and essential purpose of the State in its first beginnings. Neither is it right to say that before the State arose there was nothing to secure the enforcement of men’s natural rights. The reason and conscience of man must always have been operative, and where these were not sufficient there was available the strong rule of the pater-familias, which, as against the individual delinquent, could count in every case on the loyal support of the whole tribal community.[66] (emphasis added)

Thus, the primitive family constituted a natural organic society governed by the head of the family, who enforced moral social conventions discerned through the use of right reason as binding on the entire extended family.

Men, says [Sir John] Spelman [(1594–1643), a prominent English Historian], were never at any time free from subjection of some kind. Man is not born free, he is born into subjection, if only to his parents. The notion that government was deliberately set up by a mob of free people is absurd.[67]

History does not afford a single instance in which a State has really been formed by a contract or compact between individuals. “For practical politics this theory is in the highest degree dangerous, since it exposes the state to the caprice of individuals” or mob psychology. Indeed, this theory was one of the major contributing factors to the French Revolution of 1789.[68] The most evident reasons for its invalidity are: (1) that primitive man would have scarcely known how to draw up a political contract a la eighteenth century “enlightenment” of Rousseau, having nothing in, their experience upon which to model such a contract; (2) moreover, men in such an atomistic individualistic state of continual unconscionable warfare with one another, knowing no moral bounds or limits, would have scarcely been likely to meet peacefully and adopt political conventions or a moral code to govern their mutual relations, even if they had the sophisticated model propounded by the eighteenth century “philosophers”. In sum, the theories of Rousseau, Hobbes, and all the rest are illogical and influenced by the cultural conditions of their own time:

A contract-made State would be exceedingly difficult in the primeval period, first, because in that period men had no experience of the State and no idea of what it was like, whereas now there are States of every model to be copied; and secondly, because in the primeval period it would have been difficult to superimpose on the family organization another organization independent of the first and ruled by a different head. To primeval man the superseding of the great tribal organization based on the permanent link of the blood-tie, by another organization based on a mere temporary will-act of the citizens, would seem a wholly superfluous and absurd procedure.

The founding of a State by contract would, therefore, be exceedingly difficult in ancient times. On the other hand, the expansion of the family into the State was a normal, a necessary, and a natural procedure. The family had to expand into the tribe, and the tribe, granted that it progressed at all, had to expand into the condition of a State. It is for this reason that Aristotle speaks of the family origin of the State as “most in accordance with nature” and, therefore, as the normal manner in which the early States must have appeared. Where, therefore, the authors of the social – contract theory err is in representing as normal and universal a procedure which, if it ever existed, could never be more than accidental and exceptional.

But they are guilty of a further and more important misrepresentation still. As we have already pointed out, the authors of the theory of a primeval “state of nature” in which neither law nor rights obtained, for the most part do not regard this condition as an historical reality. Neither do they consider the social – compact as an historical reality. Their sole purpose in developing this second part of the theory is to show that the authority of the State is based upon the consent of the citizens. Now in the next chapter it will be shown that the – authority of the State, even where the State is founded, as in exceptional cases it has been founded, by compact on the part of the citizens, is never based or grounded upon such contract, but on nature, i.e. the natural necessities which it is the essential purpose of the State to supply. The State may in particular instances take its rise, as marriage and the family take their rise, in contract, but the authority of the State, just like the authority of the family, is grounded on nature, on the natural position of the ruler in one case and the parents in the other; and, therefore, the theory of the social-contract is wrong, not only as an historical account of how the State must necessarily have arisen in the beginning, but also as a theory of the ground of political authority.[69] (emphasis added)

The greatest difficulty for those of the Judeo-Christian religious tradition concerning the social contract theory of popular sovereignty is the implicit denial in this theory that there is a genuine order in the universe that constitutes the end of human existence, and that this order, which exists independently of human will or positive law, is revealed to man in the form of the natural law that arises from the order of the organic nature of things themselves. The natural law, as the basic and critical norm for all written legal systems, is monistic, while the social contract theory of popular sovereignty is pluralistic, arising out of the wills of the proletarian masses contracting to create the peoples’ republic. Under the former theory, justice, fairness and equitable rights exist as immortal realities. Under this later pluralistic theory all order and law is purely man-made and essentially arbitrary according to whim.

The Rousseauist theory is that by obeying the duly formed “general will” (volonte generale) in a majority decision, we actually obey only our own will, though perhaps an improperly informed will, if we belong to the out-voted minority.[70] The Rousseauist’s doctrine is that the essence of law is the arbitrary will of the majority constituting the “general will” (volonte generale) of the whole society, which can do anything since it does not accept the natural law as a higher moral law governing the State. In our own time, Chairman Mao terms this “thinking with the masses.” Rousseau and the individualist philosophers of the French Revolution identify the wills of individuals with the “general will” as their justification of coercive political authority.

Thus, the social contract theory of popular sovereignty legitimizes the absolute power of the will of the majority.[71] This is the essence of positivism, where the exclusive criteria of law is that it emanates from the legislative organ in a constitutionally prescribed form. Popular sovereignty creates a new leviathan: the absolute sovereignty of majorities. Indeed, the rulers of such States employ Caesarian plebiscites to legitimize actions that are otherwise clearly immoral (i.e., Nazi Germany and the various Communist States). Popular sovereignty substitutes for traditional Christian monarchy limited by natural law and the Scripture (and by papal authority in Catholic monarchies), and the democratic absolutism of majority votes to decide ultimate questions of truth and matters of right and wrong. Under the Rousseauist theory of popular sovereignty, the “general will” can never be wrong because it is democratic.

The theory of popular sovereignty was severely criticized by Pope Leo XIII in the encyclical Diuturnam illud:

The Pope criticizes it because it is so utterly individualistic. It presumes that political authority originates wholly in the free consent and makes this the exclusive and sufficient cause of political authority. It argues that political authority is nothing else than the sum of the conceded rights of the individuals, which consequently can be demanded back again at the arbitrary will of the individuals. Leo XIII says that a stable basis of political life would be impossible under such a theory, and the consequence would be permanent disorder. Furthermore – and this is its deistic or even atheistic basis – this theory denies that political authority has any relation, either as concerns origin or exercise, to God and God’s will or to eternal and natural law; it practically and theoretically places a majority decision in the place of God. Therefore its basis is a rationalism that regards human reason as the autonomous source of all truth and morality. It is this kind of philosophical justification of popular sovereignty that Leo XIII again and again refutes, pointing out that it leads to the disease of communism, the gravedigger of state, and civilization.[72] (emphasis added)

Leo XIII is undoubtedly correct because if the bourgeoisie have the “right” under the social contract theory of popular sovereignty to overthrow the legitimate Christian monarch and establish a secular republic, the proletarian masses constituting the actual majority of the population have an even greater right to overthrow the bourgeoisie laicist republic and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat through destructive mass revolutions of an atheistic and materialistic character. Acting under the concept of the “general will,” an elite segment of the proletariat, the Communist Party, assumes direction of the proletarian masses on the grounds that the wills of individual members of the proletariat, who may be opposed to the revolution, are uninformed, tricked by bourgeois propaganda, and are opposed to their own class interests. The “general will” of the proletariat, properly informed by the study of proletarian science (i.e., the doctrines of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Chairman Mao), must necessarily favor their own class interests in the form of a violent revolution against the bourgeois.

In essence, under the “general will” concept of popular sovereignty, the Communist Party has the right to assume leadership of the proletariat and create a revolution even against the actual opposition of the majority of the proletariat: a rationalistic analysis of the proletariat’s economic situation vis-à-vis the bourgeois must necessarily lead the proletariat to oppose the bourgeois in its own best class interests. Proletarians who do not favor the revolution are simply misinformed and acting contrary to their class interests. Due to this misinformation, their opinions simply cannot constitute a portion of the general will, which, according to Rousseau, is to be formed on a rational analysis of a given situation rather than on ignorance. Since a rational analysis of the proletarian class position must necessarily lead them to overthrow the bourgeois, the Communist Party may assume leadership in their name as well as a part of the informed general will, while working to educate them in the principles of proletarian science. An analysis of the writings of the leading Communist theoreticians will support this thesis. In other words, these theories can justify the wholesale slaughter of innocent people. The protective and caring nature of the de jure patriarchal or familial sovereignty, under natural law, is subverted by the Godless philosophies of popular sovereignty and social contract theory into a horrible tyranny that is so vile that it was used to justify horrible crimes against humanity.

Sadly, a major philosophical change took place in the minds of many people:

The thrones of the old European dynasties had been shaken by the hurricane of the French revolution. The divinity that was wont to hedge [fortify] a king was no longer visible to the popular eye. Stripped of his purple, each monarch of an old house stood naked, as it were, in presence of the world – a very man and nothing more. The prestige of royalty, that had for so long a time held dazzling elevation, was debased and extinguished for ever. We may say for ever; since the old sentiments of loyalty and veneration for kings, though they still exist, exist in [a] different degree to that which distinguished them in the last century. In saying this, we allude more particularly to the continental nations, which, ere they were reached by the hot breath of anarchy from France, were accustomed to look upon their sovereigns with a sort of religious awe. Viewing them as the vice-gerents of God, the people would have considered they had violated a religious duty, if they failed in the respect due to the representatives of the Most High. We can have but faint conception now of the all but adoration that used to be paid by the German people to a German king. The literature of the period bears abundant testimony of the fact. The literature of the present day bears equal testimony to the change. In the old sentiment . . . the people trusted, and their princes rarely abused: even confidence misplaced was seldom followed by confidence withdrawn. In the new sentiment there is more of caution and worldliness. The people see nothing in the powers that be but as existing by accident: that they are ordained of God, never enters their thoughts, or enters but to be denied. The people have become watchful and suspicious, rather than submissive and trusting. If obedient, they are obedient by force of law, and not by persuasion of the Gospel. They no longer leave politics exclusively to the consideration and conduct of the chiefs of the state: they consider such chiefs but as their own agents, whose acts must be vigilantly scanned, examined, criticized, and condemned, if need be. In short, the French revolution created on the continent a permanent party against royalty; it made kings subject to the many-headed tyrant [of the mob]; it gave distrust for content, exchanged Volney for the Bible; and taught the people, while sitting at home, to presume to know “what is done i’ the Capitol.”[73]

Gone was the idea that we should pray “for kings, and for all that are in authority; that we may lead a quiet and peaceful life in all godliness and honesty.” (1 Timothy 2:2). Or that the people should submit themselves “to the king, as supreme . . .” and “Thou shalt not revile . . . nor curse the ruler of thy people,” but instead “honour [that is, obey, give homage, deference, distinction, and acclaim to] the king,” or rightful ruler. (Exodus 22:28) (1 Peter 2:13, 17)

A major problem with the so-called right of self-determination in popular sovereignty is that the people can be propagandized with the false idea that they are the real sovereigns to the point that they feel so empowered that what is actually legal, lawful, and right no longer matters. Therefore tolerance for minor flaws typical of all government becomes too big to swallow. Since they consider themselves to be supreme with no law above them, they exercise unrighteous dominion – a dominion without ethical standards. This flawed philosophy of revolution was used against the great and legitimate royal houses of Europe. Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), one of the great French philosophers, asked, “Why, then, lay the blame on royalty, as though the inconveniences which are relied on to attack this system are not the same in any form of government?”[74] That is, they did not want law, they wanted license to do according to the more base desires of mankind. Therefore, they fabricated excuses for sedition.

The philosophy and politics of the French revolution began “. . . under the sign of a crime. A crime was committed in France in 1793. They killed a good and entirely likable king who was the incarnation [or embodiment] of legitimacy.”[75] This crime was replicated over and over again in the blood bath that followed the corrupt and vicious philosophies they espoused. As one author concluded, “The condemnation of the king is at the crux of our contemporary history. It symbolizes the secularization of our history and the disincarnation of the Christian God.”[76] Or, as Edmund Burke declared about the French Revolution, that it was “. . . the most extensive project ever launched against all religion, law, property, and real civil order and liberty.”[77]

The Political and Philosophical Fiction of Popular Sovereignty

The Political and Philosophical Fiction of Popular Sovereignty

Sooner or later, every foundation is exposed for what it really is. Popular sovereignty is a rejected theory that declares that the people are, or should be, the real sovereigns of all nations and should rule – they have the supreme right above all rulers and magistrates. This, of course, is the philosophy of revolution, as explained earlier. In fact, “The [French] Revolutionaries elite ‘invented’ the ‘myth’ of popular sovereignty with the intention of gutting and replacing the myth of ‘the Divine Right of Kings.’”[78] The reason why it is a myth is because it has never been realized or applied anywhere on earth, nor could it be. The state is not subject to its citizens. In every government, the real decisions are made behind closed doors by the appointed rulers. The people are not supreme or sovereign in any nation on earth and never have been. For example:

The legislative body, according to this theory [the theory of popular sovereignty], is the people, and the people are always the true sovereign [according to this view]. But the legislature obviously is not the people. The people are legally bound to obey the legislature’s commands until these are repealed by the legislature itself, no matter how oppressive or unpopular they may be. The people may of course force the repeal of such unpopular laws in time, but until the legislature sees fit to act, the people will disobey them at their peril. Popular sovereignty is, in fact, possible only in a pure democracy without representative institutions. . . . As usually employed, the phrase “popular sovereignty” contains a contradiction in terms; for, whether we like it or not, in choosing a legislature we are choosing a master, and because we choose it, it is no less a master than a monarch with hereditary title.[79]

Popular sovereignty is the rule of the people, and it is sometimes called pure democracy. It is nothing more or less than mob rule, which is never productive of good government or ever could be, because it is founded upon fads, popularity contests, whimsical and frivolous thoughts, and impulsive, reckless reasoning instead of good old common sense, fairness, and due process. The “rule of law” was designed to protect the people against popular sovereignty. The rule of law “. . . has two [main] functions: it limits government arbitrariness and power abuse, and it makes the government more rational and its policies more intelligent.”[80] The key reason why scholars do not believe in popular sovereignty is, according to Bo Li, that:

. . . without the rule of law as a limit, popular will [is] . . . corrupted by passions, emotions and short-term irrationalities. [In other words, it is corrupted by absurdities]. As such, [legal scholars] . . . demand rule of law because it helps us to behave according to our long-term [best] interest[s] and [according to good] reason.[81]

Under immediate or direct democracy, all kinds of terrible oppressions and atrocities flourish, which is the natural result when there are no laws limiting the greed and avaricious ambitions of man. The poor tyrannize the rich, those who have little or no property rob those with property, and one set of citizens arbitrarily rule over or even enslave the weak and defenseless. The founding fathers in America:

. . . regarded [“popular sovereignty”] as both their greatest accomplishment and their most serious [or dreaded] liability. For then as now, the ideal of rule by the people was exalted even as the reality of popular sovereignty was despised . . . [because it would create, according to [James] Madison [1751-1836] . . . the mortal diseases under which popular governments [democracies] have everywhere perished.

. . . It had turned out that individual rights were as insecure in a regime ruled by popular legislatures [in colonial America] as they had been under . . . [the whims of a dictator].[82]

Popular sovereignty:

. . . fell into disrepute as a reaction to its ideological uses [in the French revolution] in justifying terror and lawless dictatorship. In the last two centuries, it lost its foundational role in political theory, and disappeared from serious discussion.[83]

Pope Pius VI, commenting on the horrors and foolishness of the French revolution and popular sovereignty, declared:

. . . After having abolished the monarchy, the best of all governments, it [the French Revolution] had transferred all the public power to the people – the people . . . ever easy to deceive and to lead into every excess. . . .[84]

Jean J. Burlamaqui (1694–1748) declared:

Indeed it would be subverting all government, to make it depend on the caprice or inconstancy of the people. It would be impossible for the state to be ever settled amidst those revolutions, which would expose it so often to destruction. . . . An opinion [like popular sovereignty] . . . cannot [logically] be admitted as a principle of reasoning, or of conduct in politics.[85]

Popular sovereignty is a nice-sounding ideal, but it is really sovereignty at its worst, akin to a mindless, unthinking mob. “We may [rationally] question whether popular sovereignty is merely a fiction, a myth or a slogan [in any case it is] without much substance or reality.”[86] There is nothing solid or stable or promising about it. Yet the myth of popular sovereignty, which has never truly existed anywhere on earth in all the history of mankind, still governs much of our thinking today. It is, nevertheless, out of harmony with the law of nature, right thinking or even good old common sense.

Referendums exemplify the unsound reasoning so typical of popular sovereignty and mob rule. The use of such for anything of real importance is considered to be a grave mistake, as it is a well-known, researched fact that most people do not have the time or interest to spend hours identifying the deep, hidden issues or long-term ramifications of the proposals put before them. Most voters are not educated in Statecraft; in fact, they usually vote for very shallow reasons, like a good slogan or political spin on a subject, good looks, a most pleasing personality, a great command of speech, or a nice smile. The real issues are missed because of clever manipulations, demagoguery, or on account of the fact that a favored basketball player or celebrity promotes one popular fad over the other.

Referendums also tend to promote a kind of tyranny of the majority – a short-sighted, portentous, mob mentality along biased philosophical, religious, or ethnic lines, thereby allowing prejudice to rule and reign. Popular sovereignty (majority rule), is like having a nation composed of three citizens, two wolves and one lamb voting on what kind of meat they should eat for lunch and dinner that day. Popular sovereignty is an open invitation to numerous forms of malevolent mischief.

The general populace are not angelic, nor always wise, thoughtful or knowledgeable. In fact, “according to Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), human life would be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ in the absence of political authority [or any kind of government that maintains law and order].”[87] All civilized societies must maintain an expensive police and justice system in order that freedom and decency might have a chance of being maintained and upheld. The guilty must be punished to protect society from the rabble who have little or no conscience or integrity.

Jean J. Burlamaqui quoted Magabyses’ comments in a debate that took place thousands of years ago about what kind of government they should establish in ancient Persia. This discussion of powerful men ultimately resulted in the re-establishment of monarchy and the reign of King Darius. Magabyses declared soberly:

I believe [Otanes] is wrong in endeavouring to persuade us to trust the government to the discretion of the people; for surely nothing can be imagined more stupid and insolent, than the giddy [or whimsical] multitude. Why should we reject the power of a single man, to deliver up ourselves to the tyranny of a blind and disorderly populace? If a king set about an enterprise, he is at least capable of listening to advice; but the people are a blind monster, devoid of reason and capacity. They are strangers to decency, virtue, and their own interests. They do every thing precipitately, without judgment, and without order, resembling a rapid torrent, which cannot be stemmed. If therefore you desire the ruin of the Persians, establish a popular government.[88]

Government must be built on a more solid and stable foundation than the whimsical ideas of the thoughtless crowd.

Referendums, as a form of popular sovereignty, are likewise as reckless and irresponsible way of governing a nation. They can be especially dangerous in the wrong hands. The wording created by biased government officials can be expressed in a way that manipulates and promotes hidden agendas for special interest groups rather than what would be best for the whole nation. The long-term consequences of the proposal can easily be clouded by obscure wording. Is it any wonder that those who advocate insurrection and revolution like referendums? They can be used along with intimidation, propaganda, and/or ballot box tampering to promote their seditious ideas.

Citizen-initiated referendums are especially problematic as they prove, far too often, to be ill-conceived, knee-jerk, emotional responses to highly complex issues. As a whole – poor, short-sighted solutions generally result from such as no one is held responsible, and accountability is utterly lacking. Government by whims and fads is no government at all. It is anarchy creating confusion and disarray. It is unstable. Instead of developing unity and sound decisions, referendums tend to promote a politic of divisiveness, conflict, and harm. On the other hand, representative democracy is generally structured to facilitate compromise, moderation, and the general good of all. In sum, the use of referendums can be highly destructive of the best interests of any nation. But the worst thing about any kind of broad use of referendums is that they tend to bypass the checks and balances established to protect and safeguard our freedoms – the most precious thing we have on earth.

Referendums have also been used to unlawfully and illegally overthrow monarchies, even when those kings were lawful and a genuine benefit to the people. No matter what label was used to justify this treachery, it was an act of treason against the crown and scepter of their nations. The point is, “. . . When once the people have transferred their right to a sovereign [i.e., a monarch], they cannot, without contradiction, be supposed to continue still masters of it.”[89] “. . . Sovereignty [whether a deposed monarch or reigning republican government] cannot lose title to its territory without its consent . . . [that quality] is an invariable and necessary attribute of . . . sovereignty.”[90] In other words, “. . . they [the people] that are subjects to a monarch cannot without his leave [his permission or consent] cast off monarchy.”[91] The legal position of a legitimate monarch is impervious to deposition when permission is not freely authorized or given. The point is, under the doctrines of public international law, a ruler who is deprived of the government of his country by either an invader or revolutionaries using any kind of coercive means, such as, an unauthorized referendum, remains the legitimate de jure Sovereign of that country. As quoted before, Hugo Grotius makes it very clear that:

Contracts, or promises obtained by fraud, violence or undue fear [perpetrated by a government or some other unlawful force] entitle the injured party to full restitution. For perfect freedom from fraud or compulsion, in all our dealings, is a RIGHT which we derive from natural law and liberty.[92]

By natural law and the laws of justice, fairness, and equity, a forced referendum against a rightful government is null and void or empty of legitimacy. It also needs to be clear that the right to do this no longer belongs to the people:

. . . When the people have once transferred the ruling power [whether overtly or tacitly], they cannot licitly [legally and lawfully] revoke it at will. If they have set up a hereditary monarchy, they are obliged to leave the ruling authority with the monarch and his heirs; and the succeeding generations are likewise bound by this original transfer and compact.[93]

That is: